New England Farmers: The Cycle of Violence, Creating Hardened Killers out of Animal Lovers, and the Buried Hope for A Day No Pigs Would Die

Have you guys ever read Charlotte’s Web or better yet, The Trumpet of the Swan by E.B White. Or what about Stuart Little.

Some of the best children’s books of all time.

Let’s face it, the guy was clearly an animal lover.

Interestingly, I found a letter by E.B White about Charlotte’s Web on one of my favorite blogs, Letters of Note.

In it, he writes about how he had always loved animals, but it seems he felt ashamed of that and saw it as a weakness in himself, and I guess it never occurred to him to take a stand and become a vegetarian instead of killing the pigs he raised, even though it clearly deeply bothered him.

Instead he wrote books about what could have been.

E.B White and wife

Interesting.

It seems that was the attitude back in the day for farmers. It guess it was taboo to show any sign of “weakness” and affection for animals. Then again, they couldn’t. The job was to raise and then kill. That was their profession and their father’s and father’s fathers.

Sadly, they had to be killers.

It reminds me of another children’s book I skimmed (until the end) that at first I was horrified by, but now appreciate: A Day No Pigs Would Die by Robert Newton Peck.

It is also about a farmer…and a farmer’s son in this case (daughter in Charlotte’s Web) who grows attached to a pig he manages to save, a runt of the litter just like in Charlotte’s Web.

But unlike in Charlotte’s Web where Wilbur is safe in the end, in A Day No Pigs Would Die the father kills the pig anyway in the end in order to show his son that life is cruel and he needs to grow up and face the bitterness of life.

It seems this was almost like a twisted right of passage in the day–forcing the kids to see a slaughter. It’s like the farmers were almost bitter that they had once had their childlike love of animals crushed by their fathers, being forced to become killers, and so they perpetuated the cycle of violence on their own kids.

Every kid had to be initiated. They had to know that their job was to murder. The kids had to learn that you couldn’t love animals.

These kids who grew up among animals had to “come of age” and kill their own innocence, their spirit, their tender childlike kindness and goodness, their natural love and understanding of animals… to follow in the family tradition.

Pig farmers.

another animal lover: Robert Newton Peck

It seems many farmers were deeply hurt as children in this way and were true animal lovers at heart.

Deep down, even as adults, they still carried the glimmer of hope for a Day No Pigs Would Die deep inside them.

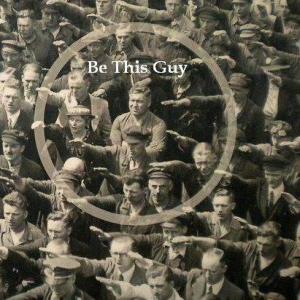

Their parents told them the world was a cold and bitter place and that’s the way life is.

But sometimes the people in charge are wrong.

Here is E.B White’s great letter:

I have been asked to tell how I came to write “Charlotte’s Web.” Well, I like animals, and it would be odd if I failed to write about them. Animals are a weakness with me, and when I got a place in the country I was quite sure animals would appear, and they did.

A farm is a peculiar problem for a man who likes animals, because the fate of most livestock is that they are murdered by their benefactors. The creatures may live serenely but they end violently, and the odor of doom hangs about them always. I have kept several pigs, starting them in spring as weanlings and carrying trays to them all through summer and fall. The relationship bothered me. Day by day I became better acquainted with my pig, and he with me, and the fact that the whole adventure pointed toward an eventual piece of double-dealing on my part lent an eerie quality to the thing. I do not like to betray a person or a creature, and I tend to agree with E.M. Forster that in these times the duty of a man, above all else, is to be reliable. It used to be clear to me, slopping a pig, that as far as the pig was concerned I could not be counted on, and this, as I say, troubled me. Anyway, the theme of “Charlotte’s Web” is that a pig shall be saved, and I have an idea that somewhere deep inside me there was a wish to that effect.

As for Charlotte herself, I had never paid much attention to spiders until a few years ago. Once you begin watching spiders, you haven’t time for much else—the word is really loaded with them. I do not find them repulsive or revolting, any more than I find anything in nature repulsive or revolting, and I think it is too bad that children are often corrupted by their elders in this hate campaign. Spiders are skilful, amusing and useful. and only in rare instances has anybody ever come to grief because of a spider.

One cold October evening I was lucky enough to see Aranea Cavatica spin her egg sac and deposit her eggs. (I did not know her name at the time, but I admired her, and later Mr. Willis J. Gertsch of the American Museum of Natural History told me her name.) When I saw that she was fixing to become a mother, I got a stepladder and an extension light and had an excellent view of the whole business. A few days later, when it was time to return to New York, not wishing to part with my spider, I took a razor blade, cut the sac adrift from the underside of the shed roof, put spider and sac in a candy box, and carried them to town. I tossed the box on my dresser. Some weeks later I was surprised and pleased to find that Charlotte’s daughters were emerging from the air holes in the cover of the box. They strung tiny lines from my comb to my brush, from my brush to my mirror, and from my mirror to my nail scissors. They were very busy and almost invisible, they were so small. We all lived together happily for a couple of weeks, and then somebody whose duty it was to dust my dresser balked, and I broke up the show.

At the present time, three of Charlotte’s granddaughters are trapping at the foot of the stairs in my barn cellar, where the morning light, coming through the east window, illuminates their embroidery and makes it seem even more wonderful than it is.

I haven’t told why I wrote the book, but I haven’t told you why I sneeze, either. A book is a sneeze.

From Letters of Note